Last week former Animatus intern and RIT student Jeremy Galante asked if he could interview me for a paper he’s writing. As someone who’s worked at an animation studio for several years, he wanted my thoughts on the state of 2D animation. I said sure, and he sent off a list of questions.

It turned out to be an enlightening experience. It forced me to think about what I’ve learned and what I hope to accomplish in the future.

Q and A with Mike Boas

Where are you from and what is your educational background?

I’ve lived in Rochester my whole life. Attended Fairport High School and graduated from SUNY Geneseo with an B.A. in art studio. (For my complete bio and credits, visit http://mikeboas.com)

At what point did you know you wanted to go into animation?

I’ve been developing my comic style of drawing since about fourth grade. In high school, I thought advertising and graphic art was for me. Later on, I realized that filmmaking was really what I should be doing. I loved movies with a passion, and my friends really pointed that out to me — I was too close to it! I graduated from college and did some research about filmmakers in Rochester, which led to interning with Animatus. After doing some ink & paint, and later animating scenes on Derf the Viking, I realized how prepared I actually was to be an animator.

First, I had always been a big animation fan. I went to see every Disney movie, had all the old Warner Bros. cartoons memorized, and kept up with the current Saturday morning and after-school shows.

Secondly, I had actually studied enough to understand the process. I remember noticing Chuck Jones‘ name on cartoons as a kid and liking his style, even before I understood what a director did. Not just WB stuff, but Riki-Tiki-Tavi, the Cricket in Times Square, The White Seal, and the Grinch. Later on I read his biographies and other interview books with animators. I had done flipbooks and animated projects on videotape as a teenager, too.

How long have you been at Animatus, and have you worked anywhere prior?

I started at Animatus in the summer of 1998. At the time, I was also working at WCMF radio in Rochester. Not a lot of opportunities to do art in radio, but it’s one of my many interests. That’s where I first got the chance to do audio editing on professional equipment.

How has your experience been at Animatus and what have been your functions?

I began working on the first Derf cartoon, The Scent of Valhalla, and since then I’ve animated large portions of the two Derf sequels and the Su & Mo series. A major challenge was in co-directing Su & Mo’s “Lost in Animation” because I had to delegate work to others and organize the production pipeline. Who gets what scene to work on, and when?

Because we’re a small studio, I’ve had the opportunity to learn how to do a little bit of everything. I know some animation students have specific goals like, “I want to be a professional modeler” or something like that. Not me. I wouldn’t say I’m an expert in any one field, but I know how to do a better than average job in many aspects of production.

Through working at Animatus, I’ve learned many programs like Photoshop, After Effects, CoolEdit, Premiere, Speed Razor, Video Toaster, and especially Macromedia Flash. I took the Animatus website from bare bones to become an impressive multi-media site. I now handle the graphic design for many website clients, and I’ve learned it all on the job. It’s great to have a site to try things out on, get familiar with what you can do, and then offer it to clients. The Animatus site has been that sort of training ground.

So I’m an animator, a webmaster, a graphic designer, and an editor. I have pretty good language skills, so I’ve written a lot of promotional materials and done internet marketing. Last year we put together a compilation DVD, so I learned about MPEG compression and DVD authoring. We now offer that to our clients as well.

What have been the most difficult projects while at Animatus?

The scary jobs are the ones that come from an ad agency at the last minute. “We just got the go ahead to do animation and we need it by Tuesday! Can you work this weekend?” There’ve been a few of those. It’s not working long hours that’s tough (although it’s not very fun) but doing boatloads of work before a client has a chance to approve it. You hope they’re going to like it, and there’s not a lot either of you can do if they don’t. It’s also teeth grinding time when you are trying to get the files rendered or finalized at the last minute. That’s usually when the computer crashes or the DVD’s won’t burn without errors.

There are also times when a client has a very specific idea of what they want. You’re sure you could do something cool (and have more fun) if they’d give you more freedom, but it’s your job to do what they ask. So that’s more of a psychological challenge.

Specifically, there have been a few challenging projects that I’m proud to have worked on. We did a short video for a Paychex conference that incorporated photographs and clip art of the American southwest, animated with a combo of Flash and After Effects. A music video we did for local singers The Dinner Dogs was our first professional Flash gig, and it still looks really great. One of the difficulties in that was exporting it to video after originally designing it for the internet. It took some work, and now I know enough to plan ahead for video output from the beginning. Recently, I did an animated tag for a Sticky Lips BBQ ad using the same methodolgy: producing with Flash and exporting as sequential images for video.

Has working in the industry given you any insight on your own projects?

Being exposed to other artists’ work is great. I’m more open to different styles of drawing and storytelling than I once was. I’ve learned that there’s a hundred different ways to do any one thing, so if I’m stuck, I can always turn to my associates for advice.

When working on your own projects, are there any artists from whom you draw inspiration?

I’m working on a piece right now that borrows the visual style of German animator Lotte Reiniger. She did these great silhouette pieces, including the first animated feature, “The Adventures of Prince Achmed.”

I love Chuck Jones’ sense of timing and character subtleties. His Bugs Bunny can get a laugh just by twitching his whiskers and looking at the audience.

Current indie animators inspire me through their marketing savvy and continuous output. Pat Smith, Bill Plympton, and Don Hertzfeldt come to mind.

I get inspired by comic strip sources, too. As a kid I was influenced by Garfield and Calvin and Hobbes. The Uncle Scrooge comics by Carl Barks are incredible, as is the Bone series by Jeff Smith. Smith worked as an animator, and you can see that expert timing on his printed pages. Anyone working in animation or comics should read Scott McCloud‘s books on sequential art: UNDERSTANDING COMICS and RE-INVENTING COMICS. He goes into the history and application of comic art, which can be helpful in understanding animation.

For studying body language, and I would encourage students to look at the acting in silent movies. Especially the works of Lon Chaney and Buster Keaton, two of my favorites.

I love the attitudes and methods of directors like Robert Rodriguez and George Lucas. Rodriguez knows what he wants to do and then just does it. He doesn’t wait for permission. Both he and Lucas have built up the means to just shoot what they want, even on a whim, and incorporate the results into their projects. Aside from whether you like the latest Star Wars movies, the craft behind them is fascinating. These movies are made using an animation mindset. Shoot one character, composite it with another character, add and environment, etc. Rodriguez has now done the same thing with Sin City. Why make a movie that looks like every other movie? Why not have some fun with the style?

Your more recent work seems to be geared towards Flash and other computer-based digital media. Do you prefer this over traditional media?

Flash is my favorite program right now. When doing character animation, I always start on paper. I’ll do straight ahead animation, or just body parts depending on the project. Then I’ll scan and bring these elements into Flash. I can build characters as if they were cut-out paper this way, with replacement heads and other parts. I love the instant feedback in Flash. You don’t need to wait for renders, as in After Effects. You can see all your layers, you have onion skinning, and you can plot moves easier than you can in some animation programs.

I’m not the most accomplished animation “artist.” I don’t have a lot of patience for perfecting fluid movements. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but personally, I usually just try to get across the main idea of each shot and get on with the story. The shortcuts involved in using Flash are suited to my attitude.

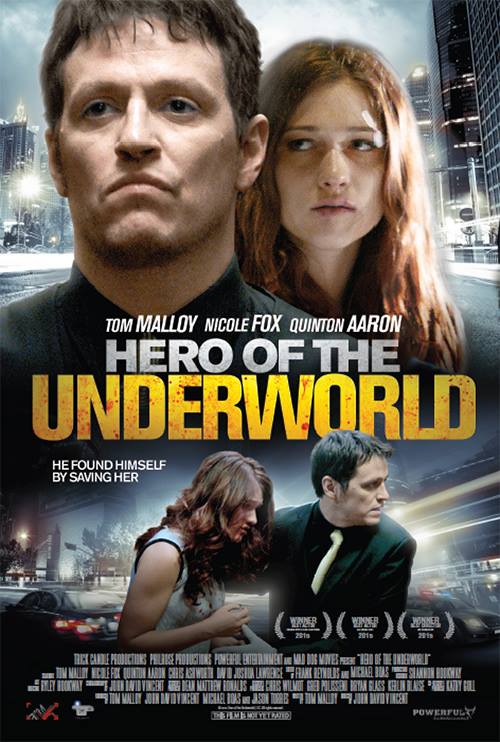

That said, Flash can be open to many styles. Many people react with surprise when they find out my “Jason” piece was done with Flash. This was something that was created in a few weeks for a fan contest. I did about a hundred really sketchy drawings and brought them into Flash. The line quality restricted me in terms of coloring, but that was fine for this project. The final product was too complicated (in terms of framerate and camera moves) for SWF output on the web, but that wasn’t the goal anyway. I exported the shots as sequential images and did the final edit in another program.

What do you still think is lacking in a program like Flash?

It’s great that the latest Flash has blur options and transitions. That’s a step in the right direction. But the major thing I’m itching for is the ability to scan directly into Flash. I like drawing and inking on paper — I’m just more comfortable that way than with a Wacom. Right now, to bring drawings into Flash, I need to scan into Photoshop, save bitmaps, import them, rotate, trace bitmap, delete extra white space… it’s a lot of wasted time. The latest version of Toonboom has some neat scanning and vectorizing functions, but it’s still not perfect.

How much time do you spend working on art?

Not enough! I feel guilty vegging out at night watching TV instead of working on my short films, but it’s tough to find the energy and the motivation. Also, carpal tunnel is an evil thing. If I’m using a mouse all day, it really hurts to use one all night.

Also, I feel I need to brush up on my figure drawing. I’ve been “cartooning” for several years now, and I feel the anatomy skills slipping away.

I use “research” as a way of procrastination, though. I watch classic (and not so classic) films, read film magazines and how-to books. I’m always learning new things.

What motivates you to make art?

Sometimes I’ll watch a bad movie and say, “Heck, I can do better than that.” Sometimes I’ll see something great that gives me something to aspire to. When Bill Plympton spoke at RIT, he mentioned that going to film festivals really gets him motivated. I’m the same way. I’ll come away from festival screenings with a hundred ideas for my own projects. Sometimes I feel satisfied if I merely storyboard something, other times I need to push myself further.

I have yet to create a film that’s entirely mine. I’ve been working with other people’s characters and storylines. So I’m itching to get my own story ideas out there. The hard part is finishing. I have a half dozen things I’m working on now, and others in the embryonic stages. If I pick a date, say a festival deadline, as a goal for completion, that can help to motivate.

What is the most challenging part about being in the industry?

Rochester is a smaller market, so drumming up work is a challenge. We need to convince potential clients that animation can offer them something that live action cannot. Sometimes this means doing some work on spec or at a reduced cost.

Pleasing a client can be tricky. Some people need to see what they don’t like before they know what they like. The thing to do is to get approvals every step of the way so there’s no surprises.

Where do you see 2D animation headed?

The media makes a big deal about the popularity of 3D over 2D films. As an independent, I don’t see the point in picking a winner. 2D isn’t going away, but we’ll see new styles push themselves forward. The “Waking Life” rotoscope style is really fascinating. Later this year, we’ll see if there’s an audience for Through a Scanner Darkly, the new Linklater film.

Those filmmakers are using proprietary software, but you can do similar work in Flash. Just bring your quicktimes in on one layer, and trace on layers above… fantastic! Some might say it’s not animation when you start with a live action source. But of course it is. The computer doesn’t do the work — a million creative decisions have to be made by the animation artist.

We’ll see more convergence of 2D and 3D. Anime productions are ahead in this regard. Movies like Ghost in the Shell 2 and Metropolis have used 3D backgrounds, 2D characters, whatever works for the story and looks cool.

The anime/manga style in general will continue to bleed into American projects. At the Animation Workshop, where I teach classes several times a year, half the kids are drawing like Yu-Gi-Oh and Dragonball. As these artists become professionals, we’ll see more American produced shows done in the “big eye” style than ever. And they’ll comment on the style while they’re doing it, like FLCL and Teen Titans have done.

Do you plan on staying in Rochester? If not, then where do you plan on taking your career?

The last few winters have really inspired me to move to a more temperate climate. No immediate plans, though.

What is your personal goal as an artist?

Not to be famous, but have quality product that people recognize. Something that I’ll mention being involved with and people will say, “You worked on that? Hey, that was pretty cool.”

What advice would you give to anyone interested in animation?

Learn the basics of hand drawn animation before getting hip deep in CG. Concepts like squash and stretch, anticipation, and gravity.

When doing character animation, give your creations personality. Get across what they’re thinking by their expressions and the way they move.

Make it a goal to enter some festivals. Keep your festival piece to ten minutes or less. Ask for feedback when you’re in the storyboard stages to be sure it makes sense to your audience.

Don’t wait for the perfect opportunity to do what you want to do. Make your own opportunities. If you don’t have a camera or computer, do flip books. Find a way to tell your stories.

Hooray! A good read! *clap clap clap clap clap*

Very cool Mike! You forgot to mention the whole “running through the fountain” hazing thing that Animatus does when they head up to Ottawa. I count that as a difficult project…